THE EU has published an update on its progress towards becoming a truly circular economy, and it reads a bit like this: a good start, but there’s a long way to go.

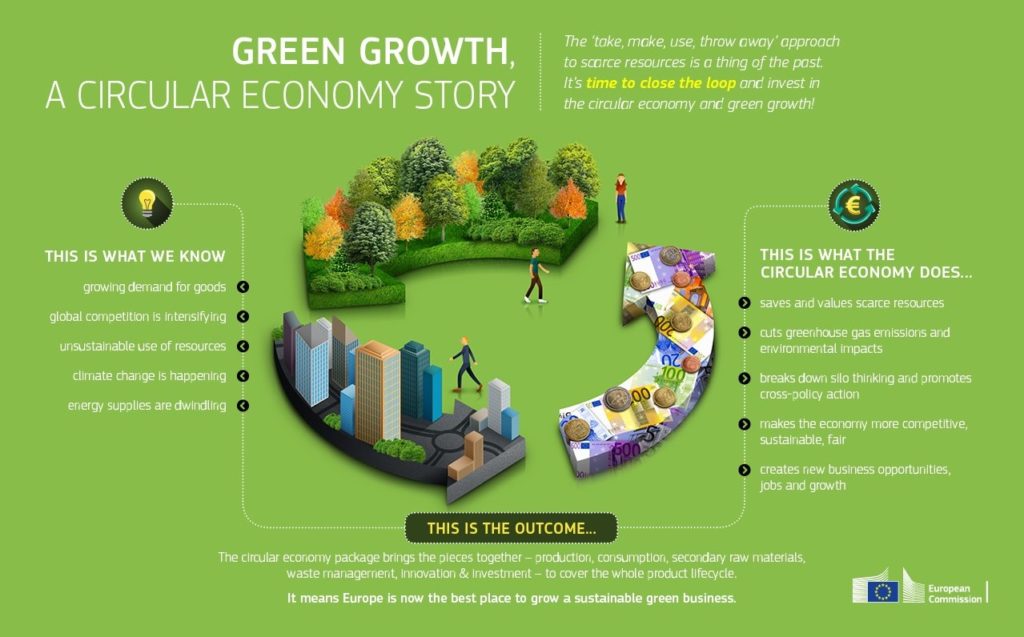

Climate change and the pressure to achieve lower carbon economies and societies is driving the need to transform business models, adjust environmental policies and introduce new thinking to “close the loop” and create value from waste.

Metals, even those with hazardous properties, play an important part in achieving this ambition. A drive to achieve a “non-toxic environment” by restricting their use in Europe risks our ability to use their unique properties to enable a transition to a low carbon economy.

European Commission’s Circular Economy

Which brings me to Socrates. Not the moral philosopher himself, but a team of EU scientists who are targeting ground-breaking ways to enhance the potential of urban mining and metals recycling to recover economically important and critical materials.

They have published a Policy Brief outlining how metals such as lead have unique properties that themselves unlock the ability to recover many other critical and rare elements by acting as a carrier enabling high-tech recycling from waste electrical equipment, various industrial residues, mixed metal scrap and more.

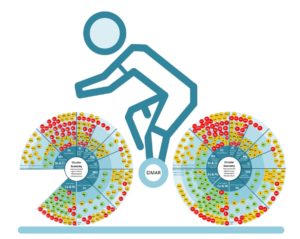

They describe the EU Circular Economy aims as a bicycle whose wheel will unceremoniously fall off if you start removing important metal spokes, such as lead, which underpin many processes, functions and entire industries.

End of the “CE ride” in case of inhibited lead metallurgy. Credit: Socrates

This whole idea may feel like something of a contradiction, allying hazardous substances with achieving a green nirvana. In fact the sort of philosophical dilemma Socrates himself might have enjoyed conjuring with.

The Policy Brief has a bold title: Lead Metallurgy is Fundamental to the Circular Economy. The central message is key to deciding if and how the EU economy can achieve circularity. And the crux of it is this. Metals recyclers extract everything from gallium, indium, used in mobile phones and solar panels, to precious metals including silver and gold, and even platinum, used in catalytic converters. But they all have one thing in common. They need lead, with its ability to dissolve and carry a multitude of elements to do it.

The good news for the Circular Economy in Europe is that the home-grown metals recycling industry is one of the most advanced and efficient in the world, creating new ‘green’ jobs and pushing the boundaries of innovation.

The bad news is that not all pieces of the EU regulatory framework jigsaw fit with Circular Economy – yet. So, when European chemicals regulators tick a box saying restrict the use of X or Y substance, it invariably has a knock-on effect which can, if un-checked, ambush the entire approach to closed-loop EU recycling.

And it is why formulaic limits on the use of important substances must not be allowed to derail the Circular Economy or future economic growth. Industry and governments can work together to achieve the right balance of controlling risks with the unique benefits those substances enable.

I’ve not doubt that this approach is something Socrates himself would approve of, philosophically speaking.

By Lisa Allen, REACH Manager